Going to try and do this book review from memory, as it was part of last week's theft.

Shake The Devil Off: A True Story of the Murder that Rocked New Orleans

by Ethan Brown

Henry Holt, 2009On the surface this is a story straight from the deepest, darkest macabre tales of New Orleans. A guy and a girl, part of the New Orleans French Quarter and bar scene get in a dispute. The guy cuts girls' limbs, puts pieces of her in various apartment appliances and he writes frightening messages all across his walls. All of this occurs only a year after Hurricane Katrina.

This is not a Hurricane Katrina book per se, more of a book about the aftereffects and emotional toll that two national tragedies wrought on the psyche of one young man.

Zack Bowen and Addie Hall's tale was spread across the local and national news as gruesome evidence of what Hurricane Katrina had wrought. I remember reading about this back in 2006 and being fascinated by what everyone else was fascinated by--not the violence, but the unusual nature of it. That it happened in the French Quarter, among folk so strange, yet so familiar to one another made it seem even more odd.

(The website Nolafugees did one of the first interesting introspective pieces about it--I think they pulled it down, but it's now in their book).

Ethan Brown seems like kind of the wrong guy to write this book, he was visiting New Orleans soon after the murder happened, and sensing a story, started interviews and later moved his family down from New York to write the story. Brown, though somewhat an opportunist, seems to have the right deposition for the legwork however. He obviously spends a lot of time at the various stomping grounds of Zack and Addie, especially at Matassa's, a grocery store in the Quarter. He is also able to convince Zack's ex-wife to speak with him along with several fellow "Quartericans"--some drug dealers, some landlords, some waiters and waitresses.

The life of Zack is fully excavated by Brown, for whatever reason (maybe it becomes clear in the last 1/8 of the book I didn't get to read) the life of Addie before New Orleans is barely touched. But we learn that Zack was a tall and nervous sort, who had a sense of depression about "mistakes he had made" before he had really made any. He had dropped out of high school in California, bounced around a bit, ended up in New Orleans bartending and eventually married a stripper named Lana. Bowen got his life together and joined the Army shortly before 9/11 and then served in Kosovo and Afghanistan. This service, as Brown makes clear, is the turning point for Bowen's life--it filled him with duty, but also filled him with post-traumatic stress, a situation that he would never fully recover from.

Brown rightly points out that Zack was involved in two of the greatest government debacles of the decade, first Afghanistan, where he witnessed children being killed and then later New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, where Zack had a front row display. But, as Brown finds, it wasn't Hurricane Katrina that Zack had a problem with, it was the post-traumatic stress worsened by Hurricane Katrina.

During the storm, Zack and Addie played "house," essentially--they befriended other holdouts in the Quarter and performed a series of odd jobs and chores during the day to make Quarter life better while hanging out with the other holdouts at night. This lasted for a month, and as every good student of Katrina knows, the Quarter was barely touched in the flooding and most that stayed practiced their drinking skills to full effect, while managing to pull off some basic Boy Scout survival skills during the day. This was the happiest and best times for Zack and Addie.

What unhinged Zack was the undoing of this war-like world, the camaraderie involved in it dissipated into a broken government system. Brown lists incidences where Zack and Addie felt disrespected by the National Guard sent to their area, as if they deserved immunity from forced evacuations and the rule of law. On Addie's side, she was plagued by extreme mood swings--sometimes violent in nature, setting her at odds with roommates and other Quarter confidantes.

Their behavior was exacerbated by the free drugs they were allowed from helping out a friend.

The very eccentricities of the people that make the French Quarter a bohemian and party mecca also make those same people unstable and volatile. The two, at least in Brown's account, go hand-in-hand.

More after the jump...

For a nice a summer reading experiment, every Thursday in July, we've looked at a hard-boiled or crime noir story. This is the last one in the series--crime noir in the widest sense, as the only crimes are the ones the characters perpetuate against themselves.

For a nice a summer reading experiment, every Thursday in July, we've looked at a hard-boiled or crime noir story. This is the last one in the series--crime noir in the widest sense, as the only crimes are the ones the characters perpetuate against themselves.

And later this afternoon, an interview with an author of a modern, kind-of crime noir story.

Previous entries:

Double Indemnity by James Cain

Dashiell Hammett/Raymond Chandler Double

The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson

Down There by David Goodis

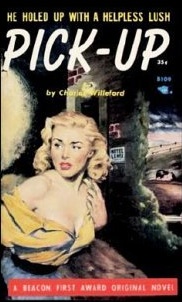

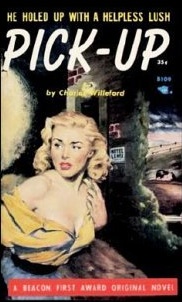

Pick-Up by Charles Willeford

Beacon Books, 1955

Charles Willeford on Wikipedia

This is that slippery slope. When there's a place, you're in it and there's no way to know how you got there and when you got there and everything looks the same. Charles Willeford creates that effect wonderfully, where every action is rationalized, makes sense, maybe not the perfect sense.

And that's the place that Harry finds himself. A few innocent drinks leads to a nice one night one stand with Helen. Harry is quickly smitten and when she re-appears the next night, he quickly throws his apron aside from his back counter restaurant job and goes drinking with Helen. And so it goes. Willeford never gives more background than necessary, so Helen and Harry wander through a few week binge of long nights, long dinners and longer drinks. A few touching moments occur in their crazy binge--Helen encourages Harry to take on painting again, his portrait of her comes out fine and flattering, his perspective of her colored through the rosiest glasses imaginable. When they hit a bottom of sorts, Harry suggests going to a hospital for free care. The questions by the doctor almost causes a double take by the reader, they are unnerving, uncommon, unimaginable in their current narrative form. It is not that Harry is the classic 'unreliable narrator,' he is more like an uninformed narrator, or a withheld narrator--details important to the story aren't important from Harry's perspective.

Pick-Up is an early look at co-dependency, a portrayal of the symbiosis needed to continue to binge, to continue to overindulge...Harry and Helen are not both alcoholics, but they need each other to convince the other one that everything will be alright.

This is also the darker side of the perceived boho lifestyle, money runs out quick, Harry does not discover an audience for his art until he becomes sensationalized through his actions, everyone wants his story, his craziness. Except we never get the impression that he's crazy, maybe a little misguided, a little uncaring, a little loose with his cash.

But the wallop that Willeford hits with in the last sentence, a whopper for 1955 shows how skilled Willeford is and everything is thrown into play again. It is in the best tradition of the classic stinger, the one punch that no one saw coming but makes all the sense in the end. How to pull it off today in a similar story is too hard, too difficult, our taboos almost fully disperse to no meaning.

This is definitely not "hard-boiled" per se and comes into the "crime noir" side of things--a stab into the deep stumble through the dark. Continually Harry fails at failing,can't even be the right kind of criminal. There's no sadness for Harry in his sorry descent, we're sad that he can't descend further, because that's all he really wants.

More after the jump...

For some summer reading, Thursdays in July will be devoted to old-school pulp-fiction crime noir stories from the 30s, 40s and 50s. Haven't read any of this stuff before, so it's high-time for a foray into the bowels of hard-boiled. The first one--Double Indemnity by James Cain.  This is essentially the classic L.A. crime story. Murder, betrayal, greed with lust--but all of those things are supposed to be in a hard-boiled crime noir story. But in Double Indemnity, Cain takes the bore out of insurance and turns it into a captivating murder plot. (Don't worry, that doesn't spoil anything). The most refreshing thing about Cain is his pace, everything is so fast. Within the first five pages, insurance man Walter Huff knows that Phyllis Nirdlinger may be up to no good, yet he can't help himself to help her. When a nifty proposal comes to rid Phyllis of her husband (still no spoiler...), Huff has a fleeting moment of crisis, told with classic Cain panache:

This is essentially the classic L.A. crime story. Murder, betrayal, greed with lust--but all of those things are supposed to be in a hard-boiled crime noir story. But in Double Indemnity, Cain takes the bore out of insurance and turns it into a captivating murder plot. (Don't worry, that doesn't spoil anything). The most refreshing thing about Cain is his pace, everything is so fast. Within the first five pages, insurance man Walter Huff knows that Phyllis Nirdlinger may be up to no good, yet he can't help himself to help her. When a nifty proposal comes to rid Phyllis of her husband (still no spoiler...), Huff has a fleeting moment of crisis, told with classic Cain panache:

"So I ran away from the edge, didn't I, and socked it into her so she knew what I meant, and left it so we could never go back to it again? I did not."

Huff is a moral man when it's convenient. Though the story is told through his eyes, it's Phyllis that's Cain's greatest creation. Cain reveals her backstory, but her intentions and desire are always kept coyly hidden. She is a femme fatale, with a scheme up each sleeve. She gives Huff control for most of the novel...until...until, well she doesn't and Cain gifts us with one of his enviable twists, something that seems so forthcoming, yet still surprising.

And what about the railroad tracks? As the above book cover shows (so it's not a spoiler either...), Huff and Phyllis commit their act on the tracks with some nifty sleight of hand and tricky alibis that only an insurance man who deals with actuarial tables on a regular basis could figure. But even with their crime taken care of--it deflates the suspense in the relationship of Phyllis and Huff, allowing Cain to send them and on us on a whole other ride.

Instead of the stubborn detective, Cain gives us Keyes, an insurance supervisor who makes logic seem too eerie. Being on Huff's back from the get-go would be too easy for Cain, instead he weaves in the nuances of the insurance profession to peg Huff. The police can't figure their murder out, only a fellow insurance junkie. But Keyes punishes Huff in a cruel, but ultimately efficient way--Keyes is devoted to the system that Huff tries to buck and so Keyes' resolution to his Huff problem is best for the company and the worst possible for Huff.

Instead of the stubborn detective, Cain gives us Keyes, an insurance supervisor who makes logic seem too eerie. Being on Huff's back from the get-go would be too easy for Cain, instead he weaves in the nuances of the insurance profession to peg Huff. The police can't figure their murder out, only a fellow insurance junkie. But Keyes punishes Huff in a cruel, but ultimately efficient way--Keyes is devoted to the system that Huff tries to buck and so Keyes' resolution to his Huff problem is best for the company and the worst possible for Huff.

Cain's style is always quick and always fleet of foot, so this is a real story, one with plot, one with characters who move, not ruminate. Yet, it brings up every ethical question under the sun. Double Indemnity is worth reading for what it is, a master original that is the source for all those copycats.

Next week: Raymond Chandler/ Dashiell Hammett shorts

Earlier editions of Missed it The First Time.

More after the jump...